- Home

- Sarah Lawton

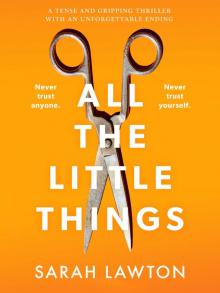

All the Little Things

All the Little Things Read online

All The Little Things

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Rachel

Vivian

Rachel

Vivian

London

Rachel

Vivian

London

Rachel

Vivian

London

Vivian

Rachel

Vivian

London

Rachel

Vivian

Rachel

London

Vivian

Rachel

London

Vivian

Rachel

Vivian

Rachel

Vivian

London

Rachel

London

Vivian

Rachel

London

Vivian

Rachel

Vivian

Rachel

Vivian

Rachel

Vivian

Rachel

Vivian

Rachel

London

Vivian

Rachel

Vivian

Rachel

London

Vivian

Rachel

Vivian

Rachel

Rachel Six Months Later

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

Cover

Table of Contents

Start of Content

For Josie, always my first reader.

Prologue

I watched my daughter die.

The days leading up to her death are seared into my memory like one of those old clicking reels of film, snapshot images flickering behind my eyelids. There, Vivian, looking up at me. There, Alex, wild-eyed and frantic.

I’d made the mistake of trusting the wrong person, again.

Never trust anyone.

Never trust yourself.

Rachel

On the night I first saw Alex the air was so hot it was almost fetid. It choked my throat and groped at me with damp fingers, slipping under my hair and arms, wrapping my legs, making my skin prickle and itch. I was late for my class.

By the time I got to the village hall most of my sign-ups had arrived: the usual suspects, a motley bunch, probably just there for the company and free biscuits. Geoff was already present, resplendent in his greying towelling robe. He always liked to strut around whipping up his crowd of admirers. Not that there was much to admire exactly, except perhaps his bravado.

He clambered onto the stage and dropped his robe with a flourish, lying back on the chaise. I noticed he had a new varicose vein on his leg, a violent burst of bulbous purple, hot against the milky white of his skin. I filed the observation away for later; the contrast of colour, for use in a painting, maybe. I did not care to look further up to where he was arranging himself to his liking.

A new name had appeared on the list I had pinned up on the village noticeboard in the hall for that week’s class. Alex. I had entertained the thought that he might be a woman, as most of my class were female, but something about the firm and determined cursive told me the hand was male. Whoever it was, they were late, and would have to take the last easel, which was directly in the line of sight of Geoff’s now spreadeagled legs.

The room settled into a hive of subdued activity. Drinks made, biscuits crunched, gossip caught up on. The hissing sound of scratching charcoal moving across parchment. I made my first round, saying nothing, merely observing how shapes were being pulled together, the creamy paper taking the gift of shade, throwing light against dark. I will never tire of watching people create.

Mrs Baxter had positioned herself away from Geoff’s business end and was sketching the great bulk of his shoulders, shading the gingery hair that covered them with sharp strokes, making them bristle in a porcine manner. Poor Geoff was an easy target for her tendency to veer into caricature. She caught my attention and nodded towards the other end of the hall. ‘Not what that one expected, I’ll bet.’ Following her gaze, I saw that the last easel had been occupied by a teenage boy who had slipped in while I wasn’t watching. ‘Do you think he was hoping for some nubile young goddess, throwing her clothes off with abandon?’

‘Probably,’ I answered with a grin, trying not to laugh. ‘It wouldn’t be the first time, would it?’ I usually asked sniggering young people to leave, but there was a gravitas about him that gave me pause.

He seemed to be made entirely of angles, sharp and new. His shoulders looked as though they were broadening in front of me, a child-man. Dark slashes of eyebrows were heavy over startling eyes that glinted like sea glass. I knew they must be extraordinary if even a hint of their colour shocked me from the small distance between us. His hand skimmed back and forth on the paper with a deftness that spoke of talent. He had a precision and stillness about him that should not belong to the young.

His eyes flicked between Geoff and the sketch in front of him, and there was no embarrassment on his face. I imagined I could hear somehow the particular sound that the heel of his hand was making as it scuffed the paper above all the others in the room, and I thought that it might smudge his drawing and bother him, this boy who moved so succinctly.

As I moved closer I could see that his face was rescued from its hard lines by his mouth, which was full, although he pressed it flat now and then with concentration. Suddenly, the very tip of his tongue peeked through, and then sharp white teeth bit down on the edge of his lip. I didn’t like the feeling that the flash of pink and those white teeth produced in me. There was something disconcerting about him. He reminded me of someone. It put me on edge so I turned away to talk to Mrs Hayward, who was struggling with perspective, as usual.

At the end of the class the dark-haired boy left as silently as he arrived. I readied the easels for the caretaker to store when he came in to lock up. No one worried that something might be stolen: a somewhat complacent mentality in a village where nothing bad ever happened.

The last easel was Alex’s. He’d left his sketch. It was exceptional. Clever strokes had built up from feather-light shimmers to a crushing, nearly tearing force, giving Geoff an almost majestic appearance. He could have been Zeus, reigning from Olympus, strong limbed and fierce of face. And yet, here was Geoff, in his essence. Portly, no shame, jolly. How had he done this? I could never have captured him like this, not in an hour. Not ever, perhaps.

This boy was special.

I took the sketch and rolled it up carefully. Closing the door to the hall behind me, it was a thirty-second walk to the Goose and Lavender. As ever, Steve, the landlord, saw me come in and pointed to the table by the door, joining me there with a bottle of wine in an ice bucket, and two glasses. The night was still warm, and the windows were all open. The breeze brought in a smell of warm asphalt and cut grass from the verge; Bill had been out with his strimmer, tidying up the green.

He sat down with a huff and squeezed around to settle opposite me. He poured us each a large glass of straw-coloured liquid, condensation forming almost immediately on the sides.

‘Thanks.’

We lifted our glasses to clink. ‘Cheers.’

‘Look at this,’ I said to him, as he sipped his drink. ‘An odd boy came into my class tonight. He’s really talented.’ I smoothed out the paper between us and he turned it around to face him, studying it for a long moment.

‘Wow.’ He traced the long line of a leg with a careful fingertip. ‘Who knew I could almost bring myself to fancy Geoff?’

‘Don’t be mean!’ I laughed.

‘God, it’s so unfair!’ said Steve

, as I pointed out some of the techniques he had used that were quite remarkable for someone his age. ‘Why can’t I draw like this? I never made it past stick men, or dogs with ten legs.’

‘Maybe you should actually come to one of my classes, then,’ I replied with a laugh, loosening up the further we got down the bottle, tensions of the day melting away.

‘How old do you think he is?’ asked Steve, leaning back in his chair and rolling his head, making his neck click revoltingly.

‘Who, Geoff? Ancient.’

‘Ha ha. No, not Geoff – your new mystery boy.’

‘Oh, I don’t know, it’s hard to tell sometimes. He’s probably a couple of years older than Vivian. Eighteen, maybe? Nineteen?’

‘Old enough then!’

‘Old enough for what?’

‘You know. There’s not a lot of choice in the village.’ He winked slyly as he said it, a slow droop of one eyelid over a hazel eye.

‘Urgh, Steve! I’m old enough to be his mother!’

‘Who says I’m talking about you?’ He leaned back and creased up with laughter. It echoed in the confines of the pub, and several people looked over and grinned themselves.

‘Can we get another bottle?’ I asked impulsively, still feeling a residue of the disquiet that Alex and his drawing had provoked in me. ‘If you don’t have to go on the bar? We haven’t had a proper catch-up for ages.’

‘Are you sure?’ Steve replied, with a grin. ‘Don’t need to get back and make sure Vivian hasn’t burnt the house down?’ He was teasing me, but we both knew how long it had taken me to let Vivian stay at home alone or go out with friends in the evenings. It had mainly been Steve’s persuasions that convinced me, but I still worried. She was getting to the age where ‘sleepovers’ were code for sitting in the park and drinking beer that they had purloined from their parents’ stashes. Steve didn’t have, or want, any children, but he was always interested in what my girl was up to.

It was strange, the friendship I had built with him. I generally kept people at arm’s length, only had acquaintances locally, but I had found myself drawn to going into the bar when Vivian had started to spend more time with her friends, wanting to feel part of a crowd when the loneliness bit. Somehow, he had picked up on it, and we had become almost close.

We took the second bottle out into the garden, which had quietened down now that people had wandered off to get their dinners. I could feel the alcohol warming my stomach and giving me a buzz of well-being that was veering toward being outright pissed.

It was late, almost ten, although the sky was still light by the time I left. I hugged Steve at the door of the pub, thinking I shouldn’t have stayed out so late. I was glad of the short walk home, my head spinning slightly. I got to the stile and pulled myself over it, muscle memory making it a smooth movement despite being tipsy. I cut across the field, breathing deeply. The air had cooled finally and smelt faintly of turned soil and honeysuckle from the hedgerow. I felt so lucky, relieved, to have found this life for us, in this safe place. Listening out for small creatures rustling in the long grass and keeping an eye out for the barn owl that roosted in the cowshed at the end of the field, I made my way across, resisting somehow the temptation to lie down and stare at the stars that were popping out against the velvet of the darkening sky.

Our cottage stood alone at the end of the path that cut through the field. It had belonged to a local farmer and he had sold it to me for a pittance. Maybe he could see I was as much a wreck as the house was, but I fixed us both up. It wasn’t the first time I’d had to rebuild myself, but I felt I got shakier each time, lacking foundations.

I almost tripped walking up the path – I never did fix that stone – and I put my hands flat on the door of our home. The blue paint was smooth and still warm from the sun. I rested my forehead against it briefly, truly regretting suggesting the second bottle of wine. My stomach roiled and dipped, and I felt guilty again for staying out so late when I should have come home to check on Vivian.

I managed to get my key in the door without too much difficulty, though I knew that the marks of previously erratic attempts after nights out with Steve were there to see in the daylight. I pushed open the door to halfway – any further would make it creak loudly – and slipped round. The house was silent, and I assumed that my girl was already asleep. I stepped out of my sandals and padded through to the kitchen, trailing my fingers on the wall for balance.

As I’d expected, the detritus of Vi’s dinner was scattered across the kitchen. The bread was open, a dirty plate abandoned by the sink. I spotted a tin of beans by the cooker and picked it up. She hadn’t eaten them all and I decided that I would, cold, with a spoon. The savoury-sweet taste reminded me that the last time I had done this was as a first year art student, getting back to my room at dawn, heavy lidded and ravenous after a night of drinking, smoking, laughing. The flavour curdled on my tongue, saccharine, and I tore off a chunk of bread to clean it away, then twisted the packet closed and put it back in its place.

Feeling a little better for the carbs I crept up the stairs as quietly as I could, and paused outside Vivian’s room. I couldn’t hear anything and no light shone around the door which, as always, was ajar. I pushed it open and carefully poked my head in. She was lying on the bed with her arms raised above her head, a ballerina pose that made her collarbones look delicate and finely drawn, shadows like spilt ink across her body. She was tiny, bird-like, and her hair shone on the pillow like silk in the moonlight. I slipped into the room to tuck her in – even though she was fifteen, I still wanted to do that, keep her safe, always – and I dropped a light kiss on her forehead, promising her silently that I would spend some quality time with her over the weekend to make up for missing her tonight.

She was the most beautiful thing I ever made.

Vivian

When I hear the door close I open my eyes and wipe away the kiss.

Mum is so weird. I hardly need tucking in when I’m nearly sixteen, and it’s boiling. At least she didn’t wake me up this time, all drunk and miserable and wanting to talk about the hospital and remembering to express our feelings, thinking I didn’t realise that her hands smoothing along my arms were looking for razor slices. Like I’d ever do that to myself. She’s the one with scars she won’t tell me about.

My phone buzzes from under the pillow. It’s Molly. She’s wittering on about this new boy she’s seen at the six-form college that’s attached to our school, and how hot he is. I suppose he’s okay-looking. I can’t say I’m particularly interested. She wants to know if I think he would like her. Who doesn’t like Molly? She could have anyone she wanted. Sounds like he’s going to be getting some random messages from her anyway: she’s managed to weasel his number off someone or other.

I lie awake for a while and listen to Mum stumbling around before collapsing into her creaky old bed. Then it all goes quiet, but I keep listening. Everyone says the countryside is so quiet compared to cities, especially to London, and I thought that too when we first moved here, but I wasn’t right. The countryside night is full of all sorts of interesting sounds, my favourite being the owl who hunts the mice who rustle in our garden. I wonder what mice taste like. I don’t hear him tonight. Instead I fall into dreams, red hands and white rooms, and I wake up late.

‘Mum!’ I yell, when I realise that it’s already gone eight o’clock. ‘Mum! You need to give me a lift!’ I rush into the bathroom and jump in the shower.

‘Mum!’ I shout again on the way back into my room to dry my hair and get my uniform on. ‘Mum, are you dead?’

‘No,’ comes a muffled voice. ‘But I might be soon.’

She’s obviously hungover after her boozeathon. Probably shouldn’t drive me, now I think about it – I don’t particularly want to die today.

‘Okay, don’t worry about the lift… I’ll call Tilly and get her brother to swing by and pick me up!’

Tilly is lazy and pays her brother to take her to school from the money she

gets doing shifts at her dad’s chippy in the village. I wouldn’t usually ask because her brother is creepy and stares at me in the car mirror, like he wants to lick me. He makes me feel sick. I’d rather walk, but I hate being late.

I quickly get my uniform on and stuff my homework in my rucksack. I haven’t got time to make any lunch so I shout to Mum that I’m taking a fiver from the pot and I hear a muffled ‘bleurgh’ in reply, which is either a yes or a yakking up; either way, it’s in my pocket as I hear Tristan’s old banger pull up outside. I open the door before he beeps and run and jump in, pulling my skirt down so he can’t ogle my legs. His piggy eyes watch me in the mirror all the way to school.

Tris drops me and Tilly off on his way to work and we stroll in chatting, eyes out for who is around. It’s nearly time for registration and we’re making our way to our classroom when Tilly nudges me and whispers, ‘Look, there’s Newboy.’

Sure enough there he is, waiting outside the entrance to his part of the building, staring at his phone. He’s doing a good job of being mysterious – he looks a bit like an eternally teenaged vampire from one of the young adult books my mum does the covers for, with thick black hair and cheekbones that Tilly would die for. His eyelashes are so long they cast a shadow.

‘Don’t stare!’ I tell her, even though I am the one doing that. ‘Molly will go mad, she’s already bagsied him.’

Molly is the prettiest one in our group, which puts her in charge. Her hair is thick and sunny coloured, and nearly down to her arse. Boys all go mad over it, because they are disgusting, and she’s always flicking it or pulling at it, or chewing on a bit, which is so gross, or twisting it around her fingers while she peeps up at them through it. Everyone loves her. She always makes an effort to be nice. I always thought to be popular you had to be cruel. Why would people want to be your friend if they weren’t afraid of what you would do to them otherwise?

We’ve been best friends since I moved here and she took me under her wing. She wasn’t so pretty then, but she is now, which suits me because being friends with the most popular girl in school means that I am too, by default, without having to put up with all the bullshit, which is good. I don’t have time to deal with more idiots than I already do.

All the Little Things

All the Little Things